Rogan

'People on the most part can smell lies' Joe Rogan

The Robespierre Experience

I sat alone on an unmade bed in a beige-and-brown bedroom. Boxes of flat-pack furniture lay scattered on the floor, some propped carelessly against the walls. Technically, it was my room, but it didn’t feel like mine. I had only just moved in, and the air carried that strange, clinical smell unfamiliar properties often have—not necessarily unpleasant, just alien. I lay back, staring up at the textured white ceiling as my eyes began to dampen. I felt utterly alone.

It was the week between Christmas and New Year’s in 2017—that odd, five-day interregnum that often leaves people adrift. It is a stretch of time suspended between two celebrations, a week no one quite knows how to handle. But unlike most years, I had no excuse for idling. The room was cluttered with reminders of tasks ignored; every unassembled box was a physical manifestation of my own paralysis.

2017 had been a brutal year—three hundred and sixty-five days of general discontent. I was struggling in a professional role for which I was noticeably out of my depth, a strain punctuated by two life-altering traumas: the death of my best friend by suicide, and the collapse of my marriage. I found myself in that alien-smelling room, pinned to the mattress by the weight of a reality I wasn’t ready to face.

At times, my mind can be a dangerous place to be left alone in. Back then, it was as toxic to my well-being as the basement of the Chernobyl power plant. My strategy for months had been to drown out the inner noise with anything that could numb it. I wasn’t brave enough to sit before a GP or mature enough to articulate my grief. Instead, I chose distraction. My iPhone became an electronic SSRI—my constant companion in the fight against myself.

Most often, I leaned on humour. Endless loops of Live at the Apollo stand-up sets filled the room, wave after wave of laughter crashing over me. Like troops charging from the trenches, the jokes came in a desperate attempt to lift the fog of depression, even if only for a moment. Eventually, the algorithms led me toward something deeper: podcasts.

The long-form format kept my mind engaged, steering it away from the aspects of the real world I wasn’t ready to confront. The informal, conversational style gave me a sense of being in dialogue with friends. I knew the companionship was artificial, but it was enough to soothe my bruised psyche and keep loneliness at bay.

I pulled the phone from my pocket and loaded the app, seeking respite from my maudlin funk. The Joe Rogan Experience title music fired up, and before I knew it, I was back in the company of ghosts. By the end of that three-hour episode, I emerged from a near-meditative state to find the furniture built, the room tidied, and the bed made. I was one step closer to finding a new horizon.

I have been an avid listener to Joe Rogan since that winter in 2017. Over the years, I have consumed hundreds of hours of his conversations. I have never met him, nor do I follow his ventures in stand-up or MMA commentary. But after so many hours of listening to him in the relaxed, informal setting the podcast fosters, I feel I know him. You cannot tune in to that much unscripted conversation without gaining a sense of the person behind the mic. I have heard him talk with friends, athletes, conspiracy theorists, and Nobel-prize-winning academics alike.

Rogan will likely stand as a key cultural figure for anyone looking back on our era. The immediacy of the present often builds fortresses around our perception of his worth, but the sheer breadth of the issues he has engaged with has woven his influence into the Western cultural fabric. His body of work is undeniably a product of this intellectual climate—and a significant mark on its history.

Yet, as I write this, I wince at the thought of my peers reading it. Because, like any historical character, “Joe the Podcast” is complicated. While the format has remained consistent over 2,000 episodes—a man led by his own curiosity—the contributors have shifted from comedic outsiders to “societal influencers” on the world stage. I am not talking about social media starlets. I mean power-political, philosophical beasts who have the ability to directly affect an individual’s sovereignty.

As the effects of this influence play out in the world’s current superpower, I find myself listening with a new kind of dread. I listen, willing the man I’ve built a parasocial relationship with to speak—to express, with urgency, a position against the platforming of beliefs that are beginning to metastasize into a cancerous ideology of ethnic and philosophical superiority.

But there is no urgency. For the first time since 2017, Rogan looks small. A man once lauded as the greatest interviewer of a generation now seems impotent to challenge even the wildest claims of his guests. After each baseless conversation that drags the discourse back to a more primitive age, he flaccidly defends it with the naive belief that every viewpoint is worth an equal hearing. He plays fast and loose with the physical and mental sacrifices our forefathers made toward modernity—the precious gifts passed down to us. He has become the ailing patriarch burning down the family estate simply because he knows of a time when society used to live in mud huts.

Vive la Révolution

Freedom of thought is essential for the continued progression of the human story. History shows that when a society loses the ability to express itself, its progression reverses. This has given free speech a sanctified position in the West. The act of speaking freely is a beautiful representation of manumission; putting up with the “bad actors” is the price we pay for the ultimately positive effects it enables.

I don’t disagree with that. But like any freedom, it must be maintained. If you do not take pride in the “housekeeping” of your platform, your fraternization with bad actors—even if driven by the purest motivations—will backfire. Unless you effectively dismantle the untruth by the conclusion of the interaction, you are playing with forces of destruction.

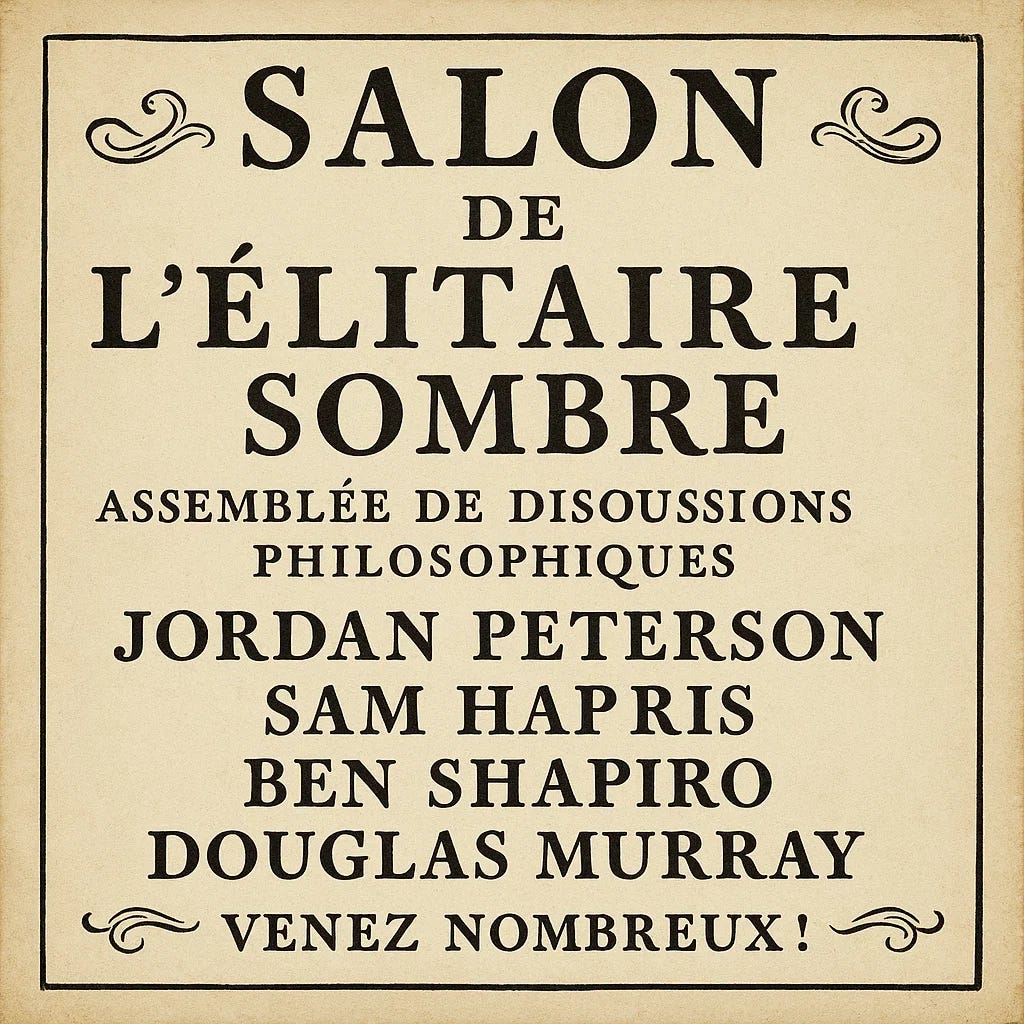

This dynamic isn’t new. Enlightenment ideals didn’t start in 18th-century Paris, but it was the development of “salon culture” that pushed egalitarianism into the mainstream. Just like the podcasts of today, thinkers like Rousseau and Voltaire wanted their thoughts heard. Salons were private, invite-only gatherings, curated by “salonnières”—razor-sharp hostesses who shaped the guest lists. They were exclusive and dripping in status, yet they fostered an oddly democratic and tolerant atmosphere.

But these weren’t just fancy parties. They were a proto-internet for the aristocracy—part newspaper, part university, part political switchboard. As things heated up in France, some of these salons morphed into something more dangerous: active breeding grounds of opposition. Radical groups like the Jacobin Club used these discussions to sharpen their arguments and test their talking points before formal debates. They used the salons to "rehearse" the revolution, seeing which emotive arguments were powerful enough to drive the masses to action.

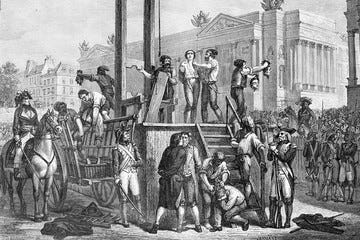

The Terror

When rhetoric becomes a form of capital, it sparks a linguistic arms race. Each speaker must push further, louder, and more extreme to be heard. The Jacobin Club was initially formed to defend Enlightenment gains and a constitutional monarchy. But in a society where the brakes are off, and where status rises in proportion to one’s rhetorical display of “purity,” words become weapons. And when words escalate without restraint, blood inevitably flows through the city squares.

In our century, “identity politics” has become the unifying bogeyman for a new version of the Jacobin Club: the Intellectual Dark Web. This loose collection of intellectuals, comedians, and internet personalities has generated thousands of hours of content around a single, ominous idea: that identity politics is a Trojan horse intended to bring about the collapse of Western institutions.

But history teaches us that no political takeover succeeds without a focal point—a leader. Faceless trends in belief eventually fade or become fuel for an opposing movement that does have a leader. And when the “victory” is won and the apparition of the enemy is defeated, the revolution has nowhere to turn but upon itself.

Just as the Jacobins splintered into warring factions, each sermonizing that their specific brand of belief was the only “correct” one, the podcast landscape has begun its own internal purge. There is no better example than the current fracturing over the war in Gaza. New media allies—who not long ago were high-fiving over their shared outrage at “wokeism”—are now turning on each other. Former comrades are being accused of being ideological stooges. The toxicity escalates with every exchange, dragging civil discourse so low that we are revisiting millennia-old accusations regarding the loyalty of Jewish citizens.

There’s no better current example of this than the fracturing over the war in Gaza. New media allies—who not long ago were high-fiving over shared outrage at identity politics and the pretension of intellectualism—are now turning on each other, accusing former comrades of being ideological stooges for the very positions they once rallied against. The same conspiracies and disinformation they once weaponised to discredit broader social movements are now aimed at each other. The toxicity escalates with every exchange, dragging civil discourse to such a low point that we find ourselves revisiting millennia-old accusations—questioning the loyalty of Jewish citizens to their country of birth.

The Robespierre Experience

The time between the founding of the Jacobin Club and the peak bloodshed of the Terror was barely four years. It was a time ripe for conspiracy—a moment when suspicion thrived because some conspiracies, like the monarchy’s collusion with foreign powers, turned out to be true. But alongside these truths, falsehoods gained lethal traction.

Conspiracies, misinformation, and endlessly escalating rhetoric in echo chambers: it feels hauntingly familiar.

Do I think there will be blood in the streets of Washington D.C. in four years? With the recent re-election of Donald Trump, a constitutional crisis seems almost inevitable by the end of his second term. How that crisis takes shape is beyond my ability to predict.

But I wonder if America, fifty years from now, will be celebrating a January 6th or 7th equivalent the way France celebrates Bastille Day—mythologizing a moment of chaos as a moment of liberation. I wonder how that prospect makes the podcast sages feel. I wonder if they realize that, like Robespierre, the architects of a rhetorical revolution are rarely the ones who survive its conclusion.